A large River Red Gum tree in front of the former Mont Park Chronic Wards, now known as ‘The Terraces’. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

There are many different species and sub-species of trees within, and surrounding the area previously known as Mont Park, now the Springthorpe Housing Estate in Macleod, an area that is the focus of our Local History Project and of this article in regard to its significantly valuable trees.

There have been a number of flora and fauna studies/surveys and reports conducted in and around this area, each for the most part, with a slightly different brief, where they were assessing a slightly different section of the area for a range of intended purposes.

In preparing to write this article, as I researched an array of reports to do with our local trees, it became increasingly apparent that two particular aspects of our trees are rather complicated to clarify for those of us that appreciate trees but have never really ‘studied’ trees.

Those two aspects were, identifying which tree is which species of tree, and perhaps even more complicated, which sub-species of tree.

The other aspect was in trying to estimate the age of a tree, particularly large living trees that pre-date the European Settlement that occurred in the area in the early 1800s.

When it comes to identifying a tree species and sub-species, the common approach is usually to look at the leaf of a tree and its shape, colour, and pattern. Other indicators include looking at the fruit, nut, or flower of the tree and its shape and colour, as well as studying the tree trunk/bark, the tree canopy, and the trees branch and overall tree structure amongst a range of other tree characteristics.

And when it comes to estimating the age of a living tree, the common approach is to estimate the Diameter at Breast Height [1] (or ‘DBH’) which in short is the circumference of the trees trunk at a height of 1.4 metres divided by Pi (or 3.14159).

Once the DBH is established, it is then multiplied by a ‘Growth Rate/Ratio’ that varies from species to species; a ratio that no doubt varies within a tree sub-species depending upon the local terrain and prevailing elements. Growth Rate is heavily dependent upon weather patterns as well, in the case of old River Red Gums, across centuries.

So, for the purpose of this article I was fortunate to receive a little assistance from a few people that are more educated than I am with regard to the species and sub-species of many of the trees around here. I also relied heavily on the wealth of information found in numerous Arborist Surveys.

Even then I have made ‘estimations only’ of the age of trees in some cases albeit that in the case of trees such as the Sugar Gum trees that form the Avenue of Honour in Cherry Street, we know for a fact that the larger trees in that line/stand of trees are all about 100 years old given that we know that they were all planted in 1919.

However, even in knowing this fact, the DBH of the two groups of Sugar Gum trees that were planted at the same time (in 1919, with a second planting in the mid 1900s) varies from tree to tree by about 10% – 15%.

In fact, of the 24 or so Sugar Gum trees that appear to have been planted as the Avenue of Honour in 1919 that are still there, most them vary in terms of their circumference from about 3 metres up to about 3.8 metres (a DBH range of about 0.95 metres up to about 1.21 metres).

Similarly, the 16 trees in the Avenue of Honour that also remain there from what appears to have all been part of the mid 1900s planting, vary in terms of their circumference from about 2.1 metres up to about 2.7 metres in circumference (a DBH range of about 0.67 metres up to about 0.86 metres).

So as mentioned, I have relied quite a bit on information contained within a number of the local tree surveys. These surveys have been completed over the past decades by Arborists that were for the most part engaged by local Councils or the land developers of the area.

One such tree survey was conducted in 1999 for the land developer Urban Pacific by the Arboricultural Consultants TREElogic [2].

This survey was carried out after the area had been closed down as a hospital precinct and was in the process of being developed into a housing estate, and where the clear intention by the developers was to preserve and where possible incorporate as much of the existing highly rated tree-scape as possible (see picture below) as well as the re-purposing of many of the hospital and hospital related buildings in the area as well (most of which are heritage listed).

A tree on Linaker Drive and the nature strip and pathway that was intentionally contoured around it. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

In terms of referring to the 1999 TREElogic tree survey, the Gresswell Forest, Hill & Habitat Link, the Strathallan Golf Course, and all of the La Trobe University area, as well as the former Larundel precinct were not included in this survey, a survey that focussed largely on the area and landscape that was to become the Springthorpe Housing Estate build area.

The primary purpose of this extensive and rigorous 1999 tree survey was to establish the health and retention value of each significant/valuable tree in the area prior to the site being developed, with the aim of retaining the areas bush/country aesthetic, while at the same time ensuring that only the healthiest and most suitable of trees were retained within the development area. In some cases, scheduled maintenance of many trees was to be carried out so as to ensure their health and long term viability and survival within a residential environment.

This 1999 tree survey found that there were 4,338 trees in the area that were either approximately 1 metre or more in circumference, or were smaller than 1 metre in circumference but were considered ‘significant’ to the area.

Of the 4,338 trees identified using the above criteria, there were 253 different species of tree, including Eucalyptus, Pine, Cypress, Palms, Acacia (Wattles), Melaleuca, Grevillia, Elm and Photinia trees.

And within these species of trees were countless sub-species of tree, for example, within the Eucalyptus (or ‘Gum’) tree family were many varied sub-species i.e. Red Gum, Sugar Gum, Swamp Gum, Manna Gum etc (see Table 1. below).

Each of these 253 different tree species had a point of origin (or area of established) that for the purposes of the survey was defined as:

‘Indigenous’ (i.e. the species originated within our local environment) or

‘Native’ (i.e. the species originated within Australia) or

‘Exotic’ (i.e. the species originated within a country other than Australia).

Far and away the most prevalent tree species in the area was (and still is) the indigenous River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) of which the survey noted there were 1,289 River Red Gums in the surveyed area, with of course many more River Red Gums in the surrounding areas including the forests, hill, Habitat Link, Sanctuary, Reserves and Parks that the survey did not look at nor assess.

The second most prevalent tree species in the surveyed area was the Exotic Narrow Leaf Ash (or Fraxinus angustifolia – sub-species angustifolia) of which there were 338 in the area.

However, these trees were seemingly deemed as ‘expendable’ by the developers of the Estate as they were believed to pose a degree of ongoing threat to the local indigenous flora, and many, if not nearly all these 338 trees were removed in the early stages of the development of the Estate.

The third most prevalent species in the assessed area was the Exotic (and somewhat enchanting) Monterey Pine (or Pinus radiata – see below) of which there were 246. A large row still exist, along with two other Exotic Pine species, namely the Canary Island Pine (or Pinus canariensis) and the Aleppo Pine (or Pinus halepensis) behind The Terraces building to the south of the surveyed area.

These pine tree species were planted here in the Mont Park Hospital precinct by renowned landscape gardener Mr Hugh Linaker https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/profile-hugh-linaker/ back in the early 1900s, making the larger pines now over 100 years old.

They were planted by Hugh Linaker with the intention of being a southern windrow (or wind break) from cold southerly winds.

Monterey Pines were also used by Hugh Linaker in other parts of the Mont Park area back then as well, including as a northern boundary windrow/windbreak, with many of these Monterey Pines still standing along the northern boundary of the Strathallan Golf Club.

A Monterey Pine that formed part of the former Mont Park precincts northern windrow that remains alongside the northern end of the Strathallan Golf Club. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

A smaller but no less impressive Monterey Pine at 75 Springthorpe Boulevard. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

A second Eucalyptus tree species that was also seen as significant to the area at the time of the survey was the Native Sugar Gum (or Eucalyptus cladocalyx) that existed across the surveyed area, a stand of which importantly form ‘The Avenue of Honour’ along Cherry Street.

I will delve more into this stand of trees later in this article.

There were also 63 Exotic Canary Island Date Palms (or Phoenix canariensis) in the surveyed area back in 1999. In fact, the survey noted that these particular Date Palms were seen as ‘the signature tree’ [2] of the Mont Park site.

As a result, 23 of these mature Canary Island Date Palms [3] were transplanted within the site along Ernest Jones Drive and can still be found along much of the southern end of Ernest Jones Drive as well as in a few other locations across the area (see picture below).

A Canary Island Date Palm at the intersection of Ernest Jones Drive and The Common. 1918. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

There are a number of other significant trees in the area including this impressive Exotic Monterey Cypress (Cupressus macrocarpa) on Springthorpe Boulevard with a trunk circumference of over 4.6 metres.

The Monterey Cypress tree at 77 Springthorpe Boulevard. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

It is also noteworthy that a particularly significant and rare tree still exists in the surveyed area. This is an Exotic Brazilian Peppercorn tree (or Schinus lentiscifolius) that can be found near the former Mont Park Nurses Hostel (now used as La Trobe University Student Accommodation) in Springthorpe Boulevard.

This Brazilian Peppercorn tree is listed on the Victorian ‘Register of Significant Trees’ by the National Trust (and thus is ‘protected’) and was reportedly bought back from Europe by the landscape gardener Hugh Linaker in the early 1900s. As such it is likely to also now be close to 100 years old.

The Brazilian Peppercorn tree next to the Student Accommodation in Springthorpe Boulevard. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Whilst the area is adorned with a range of impressive indigenous, native, and exotic trees, it is the Eucalyptus tree and its various sub-species (some of which are indigenous, and some of which are native to the area) that dominate the local landscape in terms of size, prevalence, and majesty.

Listed here (Table 1) are some of the Eucalyptus tree sub-species that one sees as one wanders around the area that was once the Mont Park Hospital precinct.

A large River Red Gum tree in front of the former Mont Park Chronic Wards, now known as ‘The Terraces’. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Table 1.

River Red Gum or Eucalyptus camaldulensis (Indigenous)

Sugar Gum or Eucalyptus cladocalyx (Native)

Yellow Box or Eucalyptus melliodora (Indigenous)

Swamp Gum or Eucalyptus ovata (Indigenous)

Spotted Gum or Corymbia maculate (Native)*

Southern Mahogany Gum or Eucalyptus botryoides (Native)

Manna Gum or Eucalyptus viminalis (Indigenous)

Red Ironbark Gum or Eucalyptus sideroxylon (Native)

Silver Princess or Eucalyptus caecia (Native)

Lemon Scented Gum or Corymbia citriodora / Eucalyptus citriodora (Native)*

*There is some ongoing debate between naturalists and conservationists as to whether the Lemon Scented and Spotted Gums are in fact part of the Eucalyptus genus. [6]

A City of Banyule tree survey [3] that was also conducted in 1999 noted the existence of another species of Eucalyptus tree in the area in the form of the uncommon Indigenous Studley Park Gum (Eucalyptus x studleyensis).

These Studley Park Gums (see picture below) are a rare hybrid of a River Red Gum and a Swamp Gum and exist at the north-western end of Cherry Street Reserve.

This tree is uncommon to this area albeit there are reported to be some other Studley Park Gums in the Watsonia Army Barracks on Greensborough Road, a few in Eaglemont, and (of course) they are also found in Studley Park, Kew (near the Yarra River) but they are apparently found in very few other places.

The Studley Park Gums (centre-left) in Cherry Street Reserve. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Other Eucalyptus sub-species that perhaps stand out for their particular aesthetic in the area are the Lemon Scented and Red Ironbark Gums, and the Silver Princess.

There is an impressive stand of Lemon Scented Gums that align much of length of the roadway known as The Common within the Springthorpe Estate.

This tree has an impressive smooth light grey trunk, and of course a lemon scent. In fact, I’d suggest one take a wander along The Common one day and grab a leaf from one of these trees and ‘scratch and sniff’ it.

It is indeed a lovely scent that adds to its attractive presence.

Lemon Scented Gums line the street in The Common. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And there is the Red Ironbark Gum, with its rich dark trunk and its light green leaves (that provides a delightful contrast to the trunk in my view).

This Native Eucalyptus sub-species has been used to beautify many suburban streetscapes, and is common to this area, in particular along Breckenridge Place.

Immature Red Ironbark trees in a small Reserve in between Sugarloaf Drive and Lookout Rise. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Mature Red Ironbark Gums on Breckenridge Place in the Springthorpe Estate Macleod. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And then there is the delightful Native ‘weeping’ Eucalyptus tree known as the Silver Princess (or Eucalyptus caesia) which is a very pretty tree, particularly when in full bloom as the bees become heavily attracted to its flower. The Silver Princess is seen in some numbers around the Estate.

The Silver Princess (three images above) on the corner of Springthorpe Boulevard and Linaker Drive. 2018. Images courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

There are also medium-sized Eucalyptus trees (see picture below) that are common on many of the streetscapes/nature strips within the Springthorpe Estate.

These Eucalyptus trees are for the most part all Yellow Gums (or Eucalyptus leucoxylon) and are not to be confused with Yellow Box Gums (or Eucalyptus melliodora) that are a larger tree.

There are a variety of these Yellow Gum sub-species across the area, namely the megalocarpa, connata, and possibly some rosea as well, each with a slightly different look in terms of leaf structure and colour, nut/fruit shape, and flower colour.

Eucalyptus sub-species varieties along Gresswell Drive. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

These Eucalyptus tree varieties were planted initially by the Springthorpe Estate developers back in the early 2000s with more planted later by Darebin Council in other areas of the Estate.

These types of trees were used as streetscape trees due to the fact that they are a medium sized Eucalyptus trees that can grow on narrow nature-strips, with the various Yellow Gum sub-species seen as providing variety and not over-uniformity of single tree types across the area, whilst at the same time retaining the overall bush-like aesthetic within the Springthorpe Estate with Yellow Gum subspecies all blending in well with the vast array of numerous other species of Eucalyptus trees, both large and small in the area and across the Estate.

In fact, when it comes to ‘streetscapes’ and ‘variety’ across the former Mont Park area, it is perhaps a highlight of the area that there are a number of roadways/streets that have their own varied characteristics and aesthetics, in large part due to the prevalence of one particular tree type and/or another.

For example, a walk or drive along Springthorpe Boulevard with its Magnolia trees is different to the journey along Ernest Jones Drive with its Monterey Palms and Bhutan Cypresses (Cupressus torulosa) trees lining the streets. And further down, whilst still on Ernest Jones Drive towards Main Drive, it has its gums trees (River Red, Spotted and Sugar Gum).

And then there is the walk/drive along The Common with its Lemon Scented Gums (and River Red Gums) which is different again to the journey along Gresswell Road with its Yellow Gum varieties.

Even along Main Drive, with its elms on the southern side of the road and its Queensland Brush Box trees on the northern side of the road near the main roundabout, that has a different feeling and look about it again as one walks or drives past.

However, it is the indigenous River Red Gum (Eucalyptus camaldulensis) and to a lesser extent the Native Sugar Gum (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) that I want to shine the spotlight on by highlighting their presence and purposes across the area.

River Red Gums no doubt hold a special place in the hearts and mind of all those that made this land, and this local area, their home, dating back to the indigenous Wurundjeri-Willam people initially, followed by the European settlers that came to the area in the early-mid 1800s, and then the thousands of residents and staff that called the Mont Park and Larundel Hospital precinct home up until the 1990s.

More recently the beauty of the River Red and Sugar Gum trees was embraced and to some extent showcased by the developers of the land who transformed the area into the Springthorpe Housing Estate for a whole new group of people/families (numbering well over a thousand people) in the early 2000s.

With so much change going on around it over the past 200 years or so, I wonder if we can try and imagine just for a moment what the large River Red Gum that stands to this very day in front of The Terraces (within the oval area on the corner of Springthorpe Boulevard and Ernest Jones Drive) has ‘seen’ over its lifetime, or what it would say if it could talk (see pic below).

The River Red Gum on the Oval in the Springthorpe Estate. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

This particular River Red Gum has been conservatively assessed as being at least ‘a few hundred’ years old, and is a most impressive looking tree it must be said albeit it has lost a number of its large branches over time.

So, given its age, it is more than likely that in the 1600s, as this River Red Gum existed where it still stands today, the indigenous Wurundjeri-Willam people lived and hunted around both it and the other River Red Gums in the area similar to it.

In fact, this River Red Gum (above) has a distinctive ‘Burl’ on it today (see pic below) and these Burls were reportedly [5] sheared off by our Indigenous people with stone implements and carved into bowls that then carried water and were used to eat food from, as well as at times being lined with fur to cradle the young.

And as the story goes, indigenous people knew that the scar left by the shearing of the Burl from the River Red Gum tree would in time heal, and that the tree would remain healthy, such was the respect indigenous people had of, and connection to, the land and its flora and fauna, including of course the River Red Gum trees.

The same River Red Gum on the Oval (as earlier pictured) showing the missing/severed large branch on the left and the Burl growing on the trunk/branch on the right. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And the connection indigenous people had with the land and its flora and fauna is perhaps best evidenced in a comment Wurundjeri Elder Bill Nicholson recently made in a public forum/presentation [6] in regard to an earlier suggestion that perhaps the ‘burning practices’ of the indigenous people ‘back in the day’ may have been detrimental to the land and/or the trees, whereupon Bill likened that suggestion to a comparison to us going into a Safeway Supermarket and buying all of our provisions, only to go outside and burn the Supermarket to the ground.

So back to the life cycle of this River Red Gum that we are highlighting. In the 1800s this particularly River Red Gum oversaw the arrival of European settlers who came and took over the maintaining of the land, and in the process probably cleared out much of the area around this tree for farming purposes, putting cows and/or sheep upon the land to graze and seek shelter under the shade provided by its branches.

An example of the local area (in this particular image as part of the Mont Park Farm in the mid 1900s prior to the La Trobe University being built) with River Red Gums in the distance providing shade and shelter for livestock. Image courtesy of the La Trobe University Library.

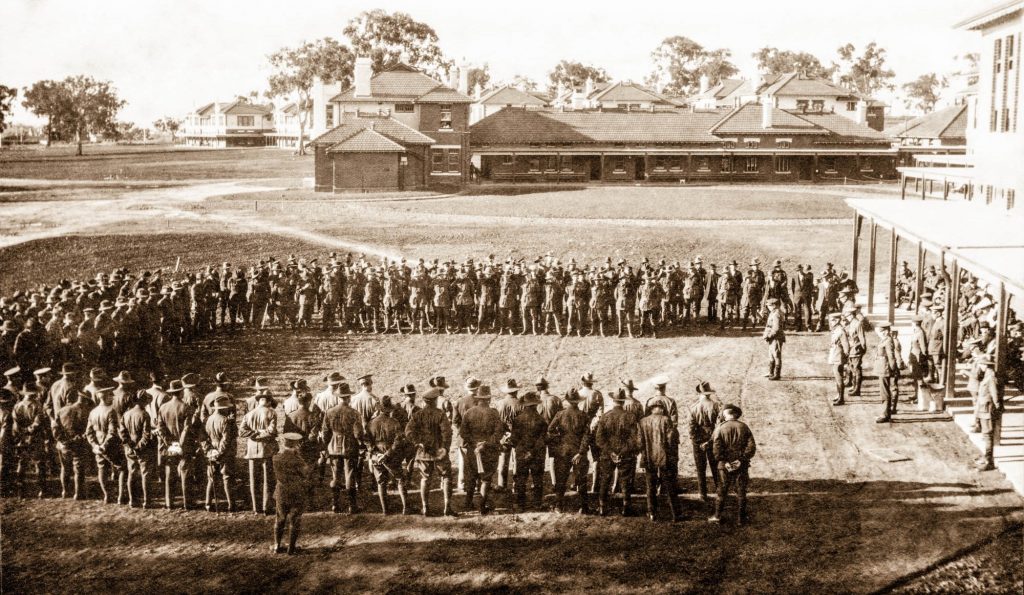

Then in the early 1900s this River Red Gum once again ‘observes’ the area progressively transformed again, when all around it is turned into a Mental Asylum with numerous Mont Park Hospital buildings constructed across the period 1910 to the late 1920s and wherein the initial use of this precinct (from around 1917 into the early 1920s) was predominantly for the rehabilitation of returned soldiers from World War I when the precinct operated much like a Military Camp (see picture below) as the Chronic Wards Building (now The Terraces) formed part of what then was called the 16th Australian General (Military) Hospital.

The front area of the then Mont Park Chronic Wards (now The Terraces) with numerous River Red Gums visible at the front, many of which are still there today. Circa 1918. Image courtesy of the Alice Broadhurst Collection per the Yarra Plenty Library.

The Troops (all returned WW1 Servicemen rehabilitating within the 16th Australian General Hospital at Mont Park at the time) ‘fall in’ to listen to a Lecture on ‘How a Soldier should behave’ at the front of the Chronic Wards and River Red Gums in the background. Circa 1918. Image courtesy of the Alice Broadhurst Collection per the Yarra Plenty Library.

Then from about the 1920s onward, this River Red Gum watched again as the 16th Australian General Hospital transitioned into the Mont Park Mental Asylum’s Chronic Wards (now known as ‘The Terraces’) as the area became home throughout much of the rest of the 1900s to Mont Park staff who lived on-site, as well as the many ‘troubled souls’ who had any number of psychological conditions and/or afflictions (who also lived here, in many cases not by choice).

Then in the early 2000s, this River Red Gum again presided over the sites dramatic transformation, this time into the Springthorpe Housing Estate that exists upon the site today and wherein this River Red Gum still stands today for all to see and admire.

So, across the many centuries, and this past century in particular, one can only imagine how many thousands of people have gazed thoughtfully into this River Red Gum’s canopy as the wind swayed branches to and fro.

Or how often some of the aforementioned ‘troubled souls’ (and/or those staff or family members who helped and cared for them) found some peace or solace looking up into the natural beauty of this River Red Gum and other ‘Silent Giants’ around here like it.

The aforementioned River Red Gum that is one the oldest and largest River Red Gums in the area in terms of trunk size, a trunk which is over 6 metres in circumference and a DBH of 1.92 metres. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Other somewhat iconic River Red Gums in the area also include the following trees (to highlight just a few) ….

The River Red Gum located at the entry to the Springthorpe Country Club on Springthorpe Boulevard. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Two large River Red Gums on the left-hand side of Ernest Jones Drive with a large Spotted Gum (also on the left side of the Drive in the middle of the image). All three trees are near the intersection of Main Drive. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And there is the lovely filtered light from the setting sun that often shines through the stand of Eucalyptus trees on the western side of Gresswell Road at late afternoon.

The stand of Eucalyptus trees at late afternoon on Gresswell Road. 2017. Image taken by Gary Cotchin.

There is also this smaller River Red Gum at the top of ‘The Cascades’ that birds repeatedly visit after rain has accumulated within the natural hollow between its live and dead branches (see picture below) that has formed into a natural birdbath for local birdlife.

The River Red Gum at the top of The Cascades in Ernest Jones Reserve, and the natural birdbath it offers local birdlife (see below). 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Two Rainbow Lorikeets taking a dip in the natural birdbath created after rain in between the live and dead branches of this River Red Gum (see arrowed above). 2018. Images courtesy of Roy Bryant.

And there are other notable Eucalyptus/Gum trees sub-species in the area as well, namely the Native Sugar Gum Trees (Eucalyptus cladocalyx) such as this one (below) that presides over the Springthorpe/Main/Gresswell/Sugarloaf Roundabout. This has a circumference of 3.5 metres and a DBH of over 1.1 metres.

The large Sugar Gum tree at the roundabout/intersection of Springthorpe Rd / Gresswell Rd / Main and Sugarloaf Drives. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And there is this Sugar Gum tree (see below) with a circumference of 5 metres and a DBH of 1.592 metres that starts off the impressive row of 41 Sugar Gum trees that collectively form the Avenue of Honour that stretches over half a kilometre along Cherry Street, Macleod.

The Sugar Gum tree next to the former Mont Park Hospital Nurses Quarters (which was built in 1923, four years after this Sugar Gum was presumably planted). This Sugar Gum is the first of the row of Sugar Gums that form The Avenue of Honour. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

The Avenue of Honour https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/the-avenue-of-honour/ was initially planted in 1919 by renowned Landscape Gardener Hugh Linaker with the help of a number of Mont Park Hospital patients.

Sugar Gum trees were planted approximately 7 metres apart in a straight line parallel to Cherry Street. Their planting was to commemorate the ‘fallen’ soldiers of World War I at a time when most of the patients within the Mont Park precinct were returned soldiers that were rehabilitating from their physical and psychological injuries from World War I.

A second lot of plantings of Sugar Gum trees occurred within The Avenue of Honour in the mid 1900s to commemorate ‘fallen’ soldiers from World War II.

I recently took a tape measure down to the Avenue of Honour and found there to still be 41 Sugar Gum trees along the row, all but one of these 41 trees measuring between 1.85 metres and 5 metres in circumference with about 22 Sugar Gum trees (still there and all presumably from the 1919 planting) averaging about 3.4 metres in circumference (or a DBH of 1.08 metres).

There are also 16 Sugar Gum trees that are still there (all presumably from the mid-1900s planting) averaging about 2.4 metres in circumference (or a DBH of 0.76 metres).

Unfortunately though there are numerous gaps at the western end of the Avenue of Honour row of trees these days, a row that stretches over half a kilometre.

The larger of these gaps span 22, 29, 36.5 and 66 metres at the western end in between an interrupted row of 7 Sugar Gum trees, with this largest gap of 66 metres occurring where a House once stood (with rubble from the now demolished house still there in the soil as well as its original driveway and front gate and path still evident on Cherry St).

But from about a third of the way down the Cherry Street hill to the eastern end of the Avenue of Honour the row is far more uniform and impressive.

Aside from one 36 metre gap, there are a row of 35 Sugar Gums there that are almost all between 7 and 7.5 metres apart except for five small gaps of 14 to 15 metres where at each of the five gaps a Sugar Gum once stood in unison with its fellow Sugar Gum trees until such time as they fell or were felled due to safety concerns to do with their condition and/or health.

In fact when we were measuring the Avenue of Honour, a local gentleman by the name of ‘Owen’ came up to us curious as to what we were up too. And after a lovely 20 or so minute chat we learned that ‘Owen’ has lived across the road for the past 40 or 50 years, and his Uncle (Uncle ‘Ted’) who served in World War I, and who he claimed sent the first ever radio message from Gallipoli to the boats that awaited offshore, had spent time at Mont Park. ‘Owen’ also explained that while Uncle ‘Ted’ was there rehabilitating from his injuries, he was one of the men that assisted Hugh Linaker in the planting of these very Sugar Gum trees in 1919.

‘Owen also spoke of how his father served in both World Wars (I and II) and how to this day, in his late 80s, he still looks up at this row of Sugar Gum trees and thinks of his father.

Suffice to say that this row of Sugar Gum trees that form the Avenue of Honour continues to provide an impressive presence in the area and a symbolic reference to the days of war and the commemoration of fallen soldiers, complementing the Victoria Cross Estate nearby that honours Victoria Cross recipients.

And the commemoration of those men that so bravely fought on our behalf in war continues to this day in the form of an Anzac Day Service that is conducted by the Watsonia RSL at this location in front of the commemorative Stone and Plaque that lie there today.

This outdoor service on or around Anzac Day each year is always well attended by a good sized audience paying their respects, and includes the attendance of numerous local dignitaries.

And whilst over time, for reasons perhaps to do with the fact that the Sugar Gum is a native tree but not ndigenous to the area, some of these Sugar Gum trees have died or have had diseases and have had to be removed or heavily pruned to ensure as best as possible their preservation, leaving these remaining 41 Sugar Gum trees standing as strong and as tall as they can together, in testament to the fallen soldiers they so ably represent.

The mid-section of the aforementioned Avenue of Honour comprising of all Sugar Gum trees that run along Cherry Street. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

In terms of the preservation and the retention of the past hundred or so years of history of the area, the Heritage preserved buildings here (most of which have now been re-purposed’by the La Trobe University) allow us to retain a strong sense of what it was like to live, work or visit this area in the past.

But it is the trees here that provide us with one of very few direct links to the past hundreds of years here, as they continue to exist and serve the exact same purpose they always have throughout previous centuries in terms of cleaning our air, providing shade and shelter and fuel for us humans, as well as providing food, shelter and a somewhat safe habitat for a vast array of local flora and fauna (including birds / kangaroos / bees / possums / sugar gliders etc.).

River Red Gums also help prevent soil erosion along waterways, including within the wetland area of the Gresswell Habitat Link. This is why River Red Gums are often found on flood plains and beside rivers and creeks, which in part at least is how they got their name.

And River Red Gums are pretty amazing survivors too.

The large River Red Gums that we still see in the area to this day have existed through the times of the Wurundjeri-Willam people. They have then survived European Settlement in the 1800s. They then survived the development of the area into a Hospital precinct, and later as a University precinct. And of more recent times they have survived the development of the area into a large Housing Estate where over 700 new homes have been built around them.

In fact River Red Gums have a wonderful way of self-survival, albeit it is an aspect of the River Red Gum that us humans most fear, that being the way in which a River Red Gum will tend to drop its often large and heavy branches in a self-pruning exercise when it is being starved of nutrients and water around and underneath it. It does this self-pruning so as to preserve what nourishment it has for the main part of the tree to survive until such time that the tree can once again flourish.

In terms of this self-pruning exercise, the contrast that exists between River Red Gums that are present within the residential area to those River Red Gums that are inside the Gresswell Forrest, Hill and Habitat Link is quite interesting when one considers how River Red Gums in the residential area have all been individually assessed and in many cases maintained and pruned back by the developers and the Council so as to ensure (as best one can) community safety by being a strong healthy tree with strong prospects of ongoing longevity in the area.

Whereas the River Red Gums in the Forrest, Hill and Habitat Link areas have in many instances been intentionally left to their own devices within an area, a habitat, and an ecology that they have always been a part of that remains relatively protected by being part of the Parks Victoria domain and ongoing responsibility.

And it is in this more natural setting that we probably see the River Red Gum in all of its true glory and rawest form with branches and limbs that have been shed by the tree often left to lay where they fall as the tree (unlike most other trees) ‘self-preserves’ via this self-pruning process.

And when these dead limbs fall to the ground, they often become home for any number of creatures (both large and small) in these somewhat protected settings, with debris from River Red Gum (including limbs and leaves, but also food and waste from those animals that seek shelter in and around tree) turning into soil nutrients at its base.

These dead limbs on the ground were also highly valued as firewood that ‘back in the day’ was used to keep us warm and to cook with.

Fallen branches and debris (and a few grazing Kangaroos) at the base of a River Red Gum in the Gresswell Habitat Link. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And when River Red Gums completely fall in some settings, they do not necessarily die nor lose purpose.

Here (pictured below) is a fallen River Red Gum in the Cherry Street Reserve that has continued to survive despite having toppled over about a year or so ago. Note the new shoots sprouting upwardly from the trunk that now lies parallel to the ground.

A toppled River Red Gum in the Cherry Street Grassland Reserve, and a burrow that now extends underneath the uplifted root base. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

New growth on this fallen River Red Gum in Cherry Street Reserve in January 2018.

The same fallen River Red Gum and the continued new growth on the same lateral trunk in July 2018. Images courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Clearly in this instance some of this tree’s roots remains embedded in the soil and is still able to extract enough nutrients from the ground up into the trunk to keep it alive.

And note how the uplifted root base has now become a home to a burrowing animal of some type as well.

And in ‘The Cascades’ Reserve (Lake) lies another fallen River Red Gum that no doubt adds to the aesthetic there but also serves as an important habitat for birdlife and water fowl to find safe-haven from surrounding threats including dogs, cats, foxes etc. (See the picture)

A fallen River Red Gum in The Cascades (Lake) 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And this River Red Gum (above) is also still alive, with well-established growth shooting vertically upward to a current height of about three metres from its partly submerged lateral trunk (see below).

The same fallen Red Gum tree as was pictured above/earlier showing the ongoing growth from this largely submerged trunk lying in The Cascades (Lake). 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And when a River Red Gum does uproot and die, the tree can still offer a great deal to the local flora and fauna.

A good example of this is a River Red Gum that has fallen and died in the middle of the Gresswell Habitat Link and is still providing a safe habitat for local fauna.

A large fallen River Red Gum in the central area of the Gresswell Habitat Link near one of the boardwalks. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

This River Red Gum (above) previously existed within an area where the natural fall of the land saw water flow down towards the Golf Club after rain (hence the boardwalk to the right). And as such, the depression/hole in the ground created by its now uplifted root base (see pic below) often fills with water and no doubt hydrates/sustains the creatures that exist in and around this fallen tree.

The water filled depression created by the uplifted root base of this fallen River Red Gum. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Also, within the Gresswell Habitat Link, is this seemingly dead River Red Gum tree that has had a large branch fall from it a while ago revealing its earlier offering as a home to bees, with their former home/hive evident within the now fractured branch (see pictures below).

The fractured River Red Gum branch, and above, the former bee hive located within the branch at Gresswell Habitat Link. 2018. Images courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And not far from here, on the slope of Gresswell Hill (just off Gresswell Road) is this River Red Gum, that despite having died a bit under a decade or so ago, remains solid and vertical and thus continues to host life in the form of any number of birds and the like in its multiple created hollows (see picture).

A dead River Red Gum and its multiple hollows on the side of Gresswell Hill near Gresswell Road. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Two Rainbow Lorikeets making a home in one of the hollowed-out branches of the dead River Red Gum on the side of Gresswell Hill. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

Another iconic River Red Gum that has died but continues to stand tall and provide a wonderful habitat for the birdlife living within it, is this River Red Gum (pictured below) at the top of ‘The Cascades’ in Ernest Jones Reserve.

A dead River Red Gum at the top of The Cascades off Ernest Jones Drive. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

In the early to mid 1900s this now dead River Red Gum (see above) presided over the Diesel and later the Electric Trains that ran up the Cherry Street Reserve hill to the Mont Park Platform and Store, https://www.montparktospringthorpe.com/the-mont-park-rail-line-and-platform/ that used to be just metres from its base (near where the large raised grassy mound is today, and where this image was taken from).

Another iconic fallen (now dead) River Red Gum is the one at the front gateway into Bundoora Park on Plenty Road Bundoora (see picture below).

A dead River Red Gum at the front of Bundoora Park. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

And when a River Red Gum does die, often its dead wood, when used as fire wood, provides us with such beauty in its final moments. Who hasn’t enjoyed those moments of reflection and deep thought as one gazes into the beautiful glowing embers of a fire that burns River Red Gum firewood?

Clearly trees, and in particular River Red Gums, are incredibly valuable to us and our broader environment across the many centuries that they can often survive and exist through.

However, despite the best attempts by those of us that truly value and treasure the worth of our River Red Gums, sadly, we cannot totally protect them.

Yes the River Red Gum can be vulnerable to some parasites/infestations as well as the weather and/or the climate and/or reduced levels of rainfall or evaporating water tables.

But as earlier indicted, they are for the most part a hardy tree that is indigenous to the area and therefore has adapted constantly to the harsh Australian summers and winters across many centuries.

But without doubt the River Red Gums biggest threat comes from us humans. Usually as a result of (understandable) safety concerns about the damage that could be caused to people and/or property due to the potential of falling heavy diseased or damaged limbs, which ironically at times only becomes an issue after we have put a house or recreational area or some sort of infrastructure in or around where the tree had always been, and suddenly the tree, that has survived across centuries, is ‘expendable’ in the eyes of some.

So, I strongly believe that we as a community need to understand just how incredibly valuable these ‘Silent Giants’ are.

And whilst our River Red Gums are amazingly tall and strong and have endured in some cases centuries of change, they are also vulnerable, and are certainly not ‘replaceable’, not in our lifetime or for that matter any number of our many future generations lifetimes.

And whilst we have tree-protectors in the form of staff and volunteers within organisations and community groups such as the Darebin Council, La Trobe Wildlife Sanctuary, Parks Victoria and Friends of the Wildlife Reserves etc. and we have tree-protections in place through policy and/or regulation and/or legislation across various levels of Government, does this really provide adequate safeguards for our large River Red Gums?

In my recent experience, probably not, as has been evidenced by the loss of some large Eucalyptus/Gum trees just in this local area over these past two years.

Some of these large River Red, Red Ironbark and Sugar Gum trees were removed after an Arborist Report had been sought and informed decisions were seemingly made as to the health of the tree and after taking into account related safety factors.

But in some instances, local trees have been removed or badly damaged in streets and/or private properties without discussion nor permission, with owners of the land and/or building or utilities contractors damaging and/or eradicating/destroying a tree or trees without going through proper process or obtaining the relevant permits, at times with little or no resultant consequence to the offending party in a few of the instances that I have become aware of around this area of late.

Another disconcerting case in point with regard to the loss of iconic and significant trees in the area is a beautiful large River Red Gum tree that adorned the side of the baseball field in the La Trobe University sporting precinct across Kingsbury Drive that ‘vanished’ earlier this year to make way for a preferred location of a new players sports change-room (which I admit is a very impressive looking building).

The huge River Red Gum (that probably pre-dated European Settlement in the area) that was within the La Trobe University playing fields (next to the Baseball field) that was completely removed in early 2018 by La Trobe University to make way for a preferred location of a players change rooms. 2018. Image courtesy of Gary Cotchin.

‘Due process’ was apparently followed in this instance with regard to this particular Red Gum tree, with the La Trobe University (who are apparently exempt from some ‘tree protection’ processes that would apply in surrounding Parks and Residential areas) lodging an Application directly with the (State) Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) for a Protected Flora Permit to remove scattered River Red Gums within that site.

La Trobe University had earlier also removed a number of other large trees of other species that circled a large section of the former football ground that is now going to be Hockey Fields.

And whilst proper process was followed by the La Trobe University in this instance, and the environmental trade-offs agreed to by the relevant bodies that were (hopefully) acting in the interests of the broader community, are these trade-off’s satisfactory (e.g. the agreement to plant seedlings along a creek bed elsewhere in the district amongst a few other similar agreements)? Or are these trade-offs disappointing compromises in some of these types of írreplaceable’ situations?

And are there times when the answer to the question regarding any intention to kill off/destroy/remove a healthy valuable tree that is hundreds of years old and as such existed well before European Settlement should just be a solid “NO” ?

There have been many community campaigns throughout the years looking to save valuable trees. Some of these campaigns have been highly successful, but many sadly not.

One such recently successful campaign was when the local ‘Save Strathallan Open Space Campaign’ (or ‘SSOSC’) sought to ensure that the beautiful open spaces in and around the Strathallan Golf Course and the nearby Gresswell Habitat Link (that formed part of the former Mont Park Hospital site) were not potentially compromised by La Trobe University’s envisaged plans to remove the Golf Club from the area and develop that area in a manner that was potentially detrimental to much of the local flora and fauna, including of course (potentially) the many massive River Red Gum trees scattered across the area.

Fortunately, in this instance, after sustained pressure from community members and other community groups that formed to become SSOSC alliance, the La Trobe University recently deferred its development plans for the area for what appears to be at least five more years, which was great news, at least for the time being, for the local environment and its flora and fauna.

However, in some other instances the removal of singular large trees played out away from community scrutiny, and the effect of the loss is at times only realised AFTER the demise of the tree (with the resultant detrimental knock-on effect to the flora and fauna that inhabited or utilised this tree).

And whilst Council practice seems to be to place Notices on trees that have been slated for removal (which is an appreciated forewarning) perhaps those that seek to remove/destroy valuable trees (such as in the earlier indicated scenarios with regard to removal of large River Red Gums), should be obliged to inform the local community of its intentions, and time afforded to the community for decisions to be reviewed and/or alternatives to be considered. And perhaps this information/notification (of an intention to remove a valuable tree) could include an obligation on the party looking to remove a valuable tree to place a Public Notice within the local media/local paper as well perhaps.

So, it is important to have protections for ‘significant’ trees, but it is equally important for those protections to be observed and enforced when necessary by the relevant Authorities prior to the sound of a chainsaws or of digging equipment.

And we the local community really do need to be the relevant authorities ‘eyes and ears’ when it comes to helping protect our beautiful trees, and in particular our large River Red Gums.

Particularly when one considers that during the period that I researched this article, it became very clear to me that a number of these same informed, educated and passionate Staff and Volunteers are (in some instances and perhaps only at times) bordering on feeling somewhat ‘burned out’ by the constant demands placed upon them out in the field and (in the case of paid staff perhaps) the burdensome obligation they at times feel when returning to the office only to find seemingly endless amounts of emails received that require a response or action that keeps them in the office for longer then they might like as well.

Clearly it is very difficult at times for our ‘protectors’ to constantly manage and monitor all that affects our local habitat, and all that goes on in our public and private spaces to do with protecting the environment, including of course our valuable trees but also our flora and fauna.

One such form of local tree protection in and around the Springthorpe Estate area that was drafted and utilised at the time the area was being developed was the establishment of Tree Protection Zones (or TPZ’s) and Critical Root Zones (or CRZ’s) that protected many trees from the consequences of being located close to digging equipment and general construction within the development site [1].

A second form of protection afforded to many trees in the area at the time of the development was the creation of Tree Preservation Zones and Tree Protection Fences which were obliged to be adhered to and were supervised by an on-site consultant Arborist during the construction of houses across the area [1].

And there were/are other forms of tree protection also available in the area these days, including the ‘Register of Significant Trees’ criteria that were established by the National Trust whereby if the relevant criteria are met and the tree is nominated for protection, it can be listed and protected by the National Trust [2] (Note: The Brazilian Peppercorn tree mentioned earlier has been listed on the Register of Significant Trees in Victoria by the National Trust in accordance with this criteria).

Additionally, significant/valuable trees can be identified and protected using other available local laws.

For example, In 2010 the City of Darebin conducted a follow-up tree assessment [4] of the earlier conducted 1999 Tree Survey carried out by TREElogic [1].

This re-assessment of all of the remaining ‘significant’ trees within the Springthorpe Estate (which does not include the grounds upon which the La Trobe University buildings sit, nor the Gresswell Forrest, Hill and Habitat Link) was conducted with the express purpose of having all these remaining ‘significant/valuable’ trees (and any additional trees that were later deemed ‘significant’ but were missed in the 1999 survey) registered as part of the protective device known as the ‘Vegetation Protection Overlay’ (or VPO).

Interestingly however, this 2010 re-assessment noted that 27 trees that had previously been noted as ‘significant’ and thus ‘protected’ had been removed in the decade prior for one reason or another.

Of the 317 trees assessed and placed on the VPO in 2010, 145 trees were located on Council grounds, 99 trees were located within residential front yards, and 73 trees were in residential backyards.

These 317 trees were grouped into the following species, namely River Red Gums (Indigenous) 124, Canary Island Date Palms (Exotic) 38, Yellow Box Gums (Indigenous) 28, Spotted Gums (Native) 14, Sugar Gum (Native) 12, Southern Mahogany Gum (Native) 8, Queensland Brush Box (Native) 7, Red Ironbark Gums (Native) 6, Swamp Gum (Indigenous) 5, Mexican Fan Palm (Exotic) 5, Mixed Indigenous Species 8, Mixed Native Species 17, and Mixed Exotic Species 45.

Once a tree was assessed as ‘significant’ and logged in the 2010 ‘City of Banyule Tree Assessment Report’ it was then protected by a number of local laws which protect significant/valuable trees, such as:

- A Vegetation Protection Overlay or ‘VPO’ as earlier mentioned (Schedule 5 – Springthorpe Significant Vegetation) which is a tool within the Victorian Planning Provisions that is applied via the Darebin Planning Scheme.

- A Development Plan Overlay or ‘DPO’ (Schedule 6 – Former Mont Park, Gresswell, Macleod and Plenty Hospital sites) that seeks to identify ‘significant’ local vegetation with the view to protecting the environmental and cultural significance of said protected vegetation.

- A Section 173 Agreement entered into under Victorian Legislation per the Planning and Environment Act (1987). A Section 173 Agreement (that has since been registered with the Land Titles Office so as to inform buyers of their obligations in regard to ‘significant trees’ within predetermined tree protection zones in the area) established these specific tree protection zones within the former Mont Park area and protects trees that had earlier been identified as ‘significant’ and catalogued by an Arborist Report (see the 2010 Darebin Report referred to above [4]). These trees are thus protected under this Section 173 Agreement with this Agreement binding upon all parties, and it can only be amended if all parties, including the Planning Minister, are willing to agree to any amendments.

So it is fair to say that numerous legislative tree protections and the like exist for trees that satisfy the relevant criteria.

And numerous public bodies and their staff, as well as community groups and their volunteers no doubt do the best they can to oversee our community interest in terms of protecting our environment and its assets, including our valuable trees in accordance with these protections.

But those of us in the local community do need to make sure that we do our bit as well and liaise with the relevant entities on any matters of concern over envisaged or actual conduct or behaviour by anyone that potentially jeopardises our local environment and its flora and fauna.

Usually this means a call to the local Council in the first instance, or in areas managed by Parks Victoria contacting them as soon as possible.

In this way I feel we as a community can best protect our ‘Silent Giants’, the beautiful River Red Gums, and play our (very important) part in protecting our delightful local environment and all of its often inter-connected and interwoven flora and fauna existences, so that our generation, and all generations to come can live within and around or visit beautiful spaces such as what we have around these parts that Mother Nature (with our help) has created in our local area for our ongoing leisure and pleasure.

References:

[1] = https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Diameter_at_breast_height

[2] = Mont Park Development Plan. Existing Tree Survey and Arboricultural Assessment. TREElogic in association with Mark Mc Wha P/L Landscape Architects. 1999.

[2] = National Trust – Victorian Heritage Database place details – 19/7/2017 – Mont Park. Classified 16/12/1992.

[3] = Tree Assessment. For Darebin City Council. Assessment of trees for VPO update in Springthorpe Estate, Macleod. 2010.

[4] = City of Banyule – Significant Tree & Vegetation Study. Prepared by the University of Melbourne, Centre for Urban Horticulture. May 1999.

[5] = ‘The Welcome Bowl’ – Heritage Trail signage at ‘Farm Vigarno’ in South Morang. Victoria. 2018.

[6] = The Wurundjeri presentation at the City of Darebin Library by Mr Bill Nicholson of the Wurundjeri Tribal Council. 8/8/18.

Thank you’s.

My thanks go to Mr David Smith of the Darebin City Council for his assistance in regard to some sections of this article, as well as to Mr William McMahon of Paroissen Grant and Associates Pty Ltd and his input including access to the 1999 TREElogic Survey.