1962 – 2022

Dr (William) Ernest Jones (1867 – 1957) was very much respected as a psychiatrist and administrator, and the Ernest Jones Clinic, the Ernest Jones Hall in Mont Park (opened in 1930), and a boulevard in Springthorpe Estate near Mont Park, are named after him.

He trained in London, graduating in 1890. After experience from his employment in asylums, he was recruited to work in Victoria, and played a pivotal role in advancing more suitable treatment and accommodation for those with mental ill health. He was initially appointed as ‘Inspector-General of the Insane’ for 5 years and ultimately served from 1905 – 1937, with the final more refined title of ‘Director of Mental Hygiene’. See Dr (William) Ernest Jones | Mont Park to Springthorpe

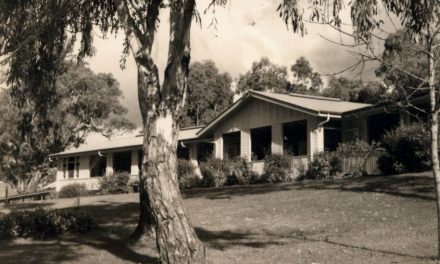

Carmel House – photo taken in 2022 (K. Andrewartha)

1962

The Ernest Jones Clinic (EJC) in Hotham Street Preston was established in 1962 as a day hospital. The Ernest Jones Clinic provided community-based psychiatric services and developed a group homes program centred around ‘Rosa Gilbert House’ and the ‘Carmel Hostel’ in Hotham Street Preston. ‘Carmel’ had been a private hospital in a two storey house with established gardens, and was purchased in 1963. EJC provided outpatient assessments and also treatments including injections of dopamine blockers to calm thoughts and mood swings, or even the more intrusive electroconvulsive therapy. Ernest Jones Clinic | findingrecords.dhhs.vic.gov.au

The Mental Health Authority Parliamentary Report of 1963 stated that Mont Park medical staff were finding that working with outpatients in the Preston clinic kept the clients from returning to hospital. Dr Grantley Wright was the Psychiatric Superintendent responsible at this time and was located at Mont Park Hospital.

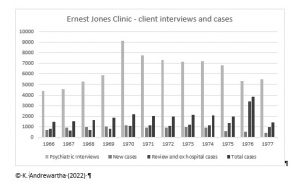

Dr B. Clark, the Consultant Psychiatrist at Ernest Jones Clinic, itemised 965 psychiatry sessions in the 1964 Annual Report. Records showed that 4887 patients attended the Clinic, and of these 1358 were new referrals. The Consultant Psychiatrist, the Medical Officer and 33 other medical staff from area hospitals had seen patients.

Outpatient narratives for the Mental Health Authority showed the client numbers at the Ernest Jones Clinic gradually increased over the next decade.

1972

Dr David Barlow in the Ernest Jones Clinic Annual Report in 1972 stated that 48% of the patients that year had come from the Mont Park Hospital, 24% from Plenty Hospital and 11% from Larundel.

Increasingly the EJC was serving a teaching function with nursing students from the Larundel Clinical School attending the outpatient program and the Day Hospital. Social Work students, Occupational Therapy students and Social Welfare trainees also engaged in training at the Ernest Jones Clinic.

An Emergency Service was instigated at EJC in 1972 for crisis intervention.

After care facilities at the local Carmel Hostel, Rosa Gilbert Flats, McCracken House and Gower Street flats continued to be administered by EJC staff.

A pharmacist was employed full time from 1972, to dispense medication including injections. Nurses from EJC visited homes to provide care in the domestic environment.

A further statement to Parliament in October 1972 provided an update on patients discharged from Larundel, who were expected to be outpatients at the Ernest Jones Clinic. There was a waiting period of 2-3 weeks, although there was capacity to take care of emergency cases.

Physical improvements to the EJC at this time, included construction of a concrete driveway to accommodate visitors and staff parking.

1976

In 1976 Carmel Hostel had residential capacity for 16 women, with 9 patients being discharged during the year, and no new admissions.

In that same year, the Rose Gilbert House had rooms for 18 females, 36 women were admitted and 25 discharged. In 1977 figures were similar with responsibility for 45 new patients and 30 ladies were discharged.

In 1976 the ‘Preston Day Hospital’ now had 88 clients as outpatients, 23 admitted during the year, and 84 discharged, with 27 patients still being looked after at the end of the year.

Mental Health Authority Parliamentary Reports beyond 1977 collected statistics in a different format and specific comments were no longer recorded to provide detailed descriptions of the activities at EJC Preston.

De-institutionalization

From the 1980s treatment in outpatient clinics for those with mental ill health, was seen as more efficient and effective than treatment in mental hospitals. Hospitals required permanent boarding fees in addition to medical fees. Patients were considered to have more freedom with community-based treatments and of course it was less expensive.

The de-institutionalization philosophy and procedures could give rise to disadvantages for patients. They needed to be carefully and suitably prepared for discharge into the care of outpatient clinics. Unfortunately some mentally ill patients relapsed into a ‘revolving door’ situation, where they were periodically hospitalized, released and without effective rehabilitation, then needed confinement in a hospital again.

A report to the Victorian Parliament in 1989 answering a question on notice, stated that EJC functions were still continuing to be:

- Assessment and early treatment of emergency and new referrals

- Rehabilitation, in the form of longer term programs in social skills and life skills

- Accommodation support programs in 6 flats and 13 group homes, currently catering for 55 residents.

$1 million in recurrent funds was allocated to EJC in the 1988 -1989 financial year. Before 1985 funding had been part of the Mont Park Hospital financial allocation.

EJC staff were fully occupied with patients and their families, with interviews, reviewing cases, therapy sessions, emergency work, and also supervising and engaging in the accommodation program for the 55 residents.

2022 – 60 years on

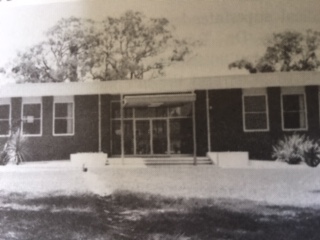

Photo of the original Ernest Jones Clinic – Provided by the State of Victoria to use to provide insight into the development of psychiatry in Victoria (Non-Commercial Use)

In a statement to the Government Royal Commission in 2020, Sandy Jeffs OAM highlighted the importance of after care facilities for patients who have been in mental health hospitals.

Sandy is a former patient of Larundel and a valuable advocate for people with mental ill health. She is the author, with Margaret Leggatt of the book ‘Out of the Madhouse. From Asylums to Caring Community?’ (2020).

Sandy Jeffs pointed out the value of social support in clinics, such as represented by the Ernest Jones Clinic. People need help to access scheduled appointments, and manage their rehabilitation. Sandy advocated group therapy and art and music therapy sessions in pleasant community surroundings as essential for a return to health. See, Community witness statement template (royalcommission.vic.gov.au)

The EJC service has evolved now into the Northern Adult Area Mental Health Service. See, Northern Adult Area Mental Health Service | Victorian Agency for Health Information (vahi.vic.gov.au)

This facility provides a range of vital clinical treatment services for adults experiencing an episode of severe mental illness and is mobilised for patients in the Whittlesea and Darebin areas. There are acute, subacute, specialist, and support mental health services. Inpatient units are located within surrounding general hospitals and Community Care Units provide 24 hour attention for those with complex needs. One of these residential services is still in Preston and such units provide Prevention and Recovery Care.

Sources:

Vic Parliamentary papers – Mental Health Authority Reports on line. For example use:

Search Results for mental health 1965 (sirsidynix.net.au

Other sources as indicated.

Thanks to Mental Health Library Victoria for assistance with finding the photo of the original Ernest Jones Clinic.